Linux Processes — A Kernel’s Perspective Explained with Clarity and Simplicity

Preface: I have been going through the book “Linux Kernel Development” by Robert Love which I highly recommend for understanding the Linux Kernel in depth. I decided to write this article to explain “Linux Processes” simply and concisely. The topic itself is broad and is not explained into the deepest of it, but essential for Linux Administrators, Developers and even Linux users to appreciate the beauty of the Kernel they make use of every day.

A Clear Definition of a Process

A process is a program amid execution.

The object code that contains the instructions for the system to execute is stored in some kind of media. When the code starts executing, a process is created then and continues to exist to the point, that the execution of the code ends.

Processes, however, are more than just the execution of code by passing it to the CPU and fetching out existing results. They are a package of systems that execute, run and store various amounts of elements and ensure smooth execution of a code with an optimal amount of resources and maintain a degree of transparency with the system. They consolidate various factors like the memory space, processor state, internal kernel data, memory mappings, threads of execution as well as global variables (in the data section).

Usually in the world of Linux, a process can be referred to as a task.

A Clear Definition of a Thread

Threads of executions are the activities that go on within a process.

A Thread has its own unique program counter, process stack, and a set of processor registers (they are very similar to process). The Kernel schedules threads, also referred to as kernel threads are executed solely in the kernel space. Traditional UNIX programs used to have only one thread for a process. Modern Operating Systems are multi-threaded and a process can spawn multiple threads to get its task done.

Linux has a unique implementation of threads: It does not differentiate between threads and processes. Linux considers threads to be a special kind of process (this can be seen clearly in the source code about the considerations of threads as a process with special modifications).

Illusion within Processes — Virtualisation of Resources

Modern Operating Systems provides two visualisations to processes:

- Virtual Processor

- Virtual Memory

A process is allocated with a Virtual Processor, so it considers that the whole system is its own space of execution and that it exists alone in the system. Virtual Memory provides the illusion of freedom to the process of allocating required memory.

In short, processes are isolated and have the illusion of being alone in the whole system.

Programs are not Processes

A Program is not a process, but a process is an active program. A program can have multiple processes and those processes can have multiple threads and child processes running. For these purposes, a lot of system calls are implemented and ensure a smooth order of execution and handle edge cases.

Process Descriptor and the Task Structure

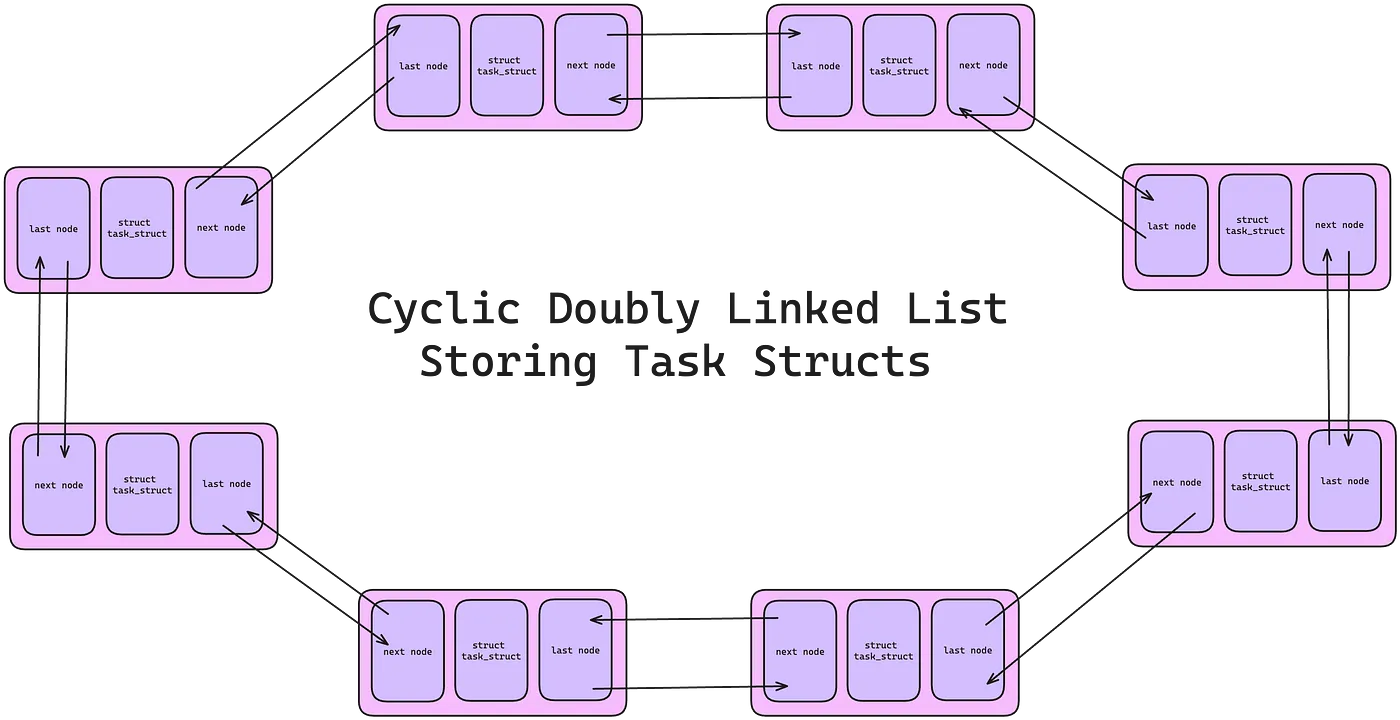

Linux Kernel stores the list of processes in a circular doubly linked list called the task list (for me, it’s amazing to see the implementation of a circular doubly linked list and imagine how new tasks will be added to the circle to increase its size).

Each element in the task list is a process descriptor and it is of the type struct task_struct which is defined in <linux/sched.h>. The process descriptor contains all the information about a specific process. The process descriptor in itself is a very big data structure but consolidates all the information the Kernel needs to know about a process. It is around 1.7 kilobytes on a 32-bit machine.

The Allocation of Process Descriptor

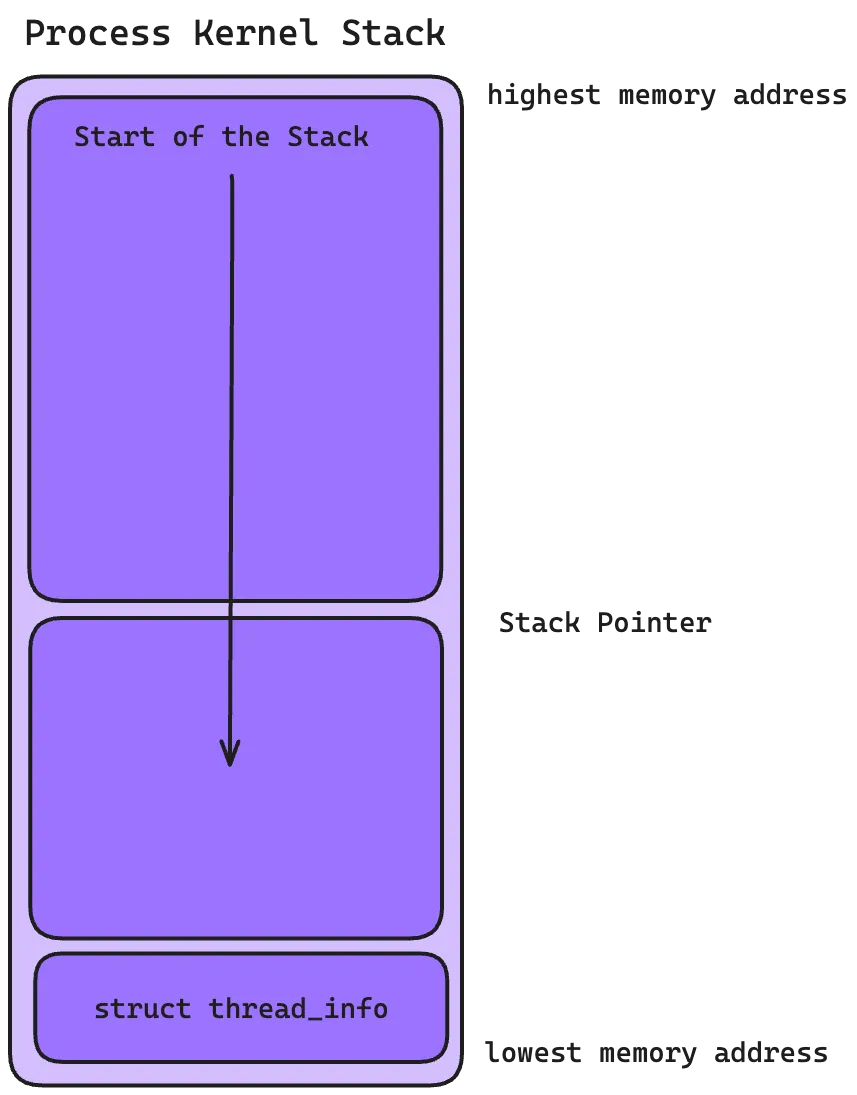

In the x86 architecture systems, the task_struct was stored at the end of the kernel stack of each process. This allowed the usage of a few registers to calculate the location of the process descriptor via the stack pointer (which saves the usage of an extra register).

For modern systems, slab allocator is used that stores a new structure struct thread_info that lives at the bottom of the stack in case of stacks growing downwards and at the top of the stack for stacks growing upwards.

struct thread_info {

struct task_struct *task; /* main task structure */

__u32 flags; /* low level flags */

__u32 status; /* thread synchronous flags */

__u32 cpu; /* current CPU */

int saved_preempt_count;

mm_segment_t addr_limit;

void __user *sysenter_return;

unsigned int sig_on_uaccess_error:1;

unsigned int uaccess_err:1; /* uaccess failed */

};

The task element of the structure is a pointer to the task’s actual task_struct.

The Process State

The state field in the process descriptor describes the current condition of the process. There are five different states and a process can exist in one of these states.

TASK_RUNNING: The task is runnable or is currently running or in a queue waiting to run. This is the only possible state for a process executing in user space (although it applies to the processes running in the kernel space too).

TASK_INTERRUPTIBLE: The process is sleeping and is waiting for some condition to exist. When that condition is reached, the process is set to TASK_RUNNING.

TASK_UNINTERRUPTIBLE: This is similar to TASK_INTERRUPTIBLE but cannot be waked with an external signal or any condition reaching a state. This is used when the process is required to wait without interruption.

__TASK_TRACED: The process is being traced by another process, such as a debugger, via ptrace.

__TASK_STOPPED: The process has been stopped or the task is not running or it’s not eligible to run. This occurs if the task receives the SIGSTOP, SIGTSTP, SIGTTIN, or SIGTTOU signal or any signal while it’s being debugged.

Conclusion

Linux Processes is a huge topic and cannot be conveyed in a single post. Although, these are a few things that Linux Operators should know to appreciate the beauty of process management in Linux. I will be incorporating a lot of topics in the future about this topic. Till then, more exploration can be done on the internet. I made this post to scratch the surface of Linux Kernel and will keep digging deep.